THE THREE PODIUMS AND BELOKI'S LAST ATTACK

author: Ander Izagirre,

Marco Pantani attacked five times on Mont Ventoux, only leader Lance Armstrong followed him on the fifth and they rode together to the summit. In the last kilometre, Armstrong clearly slowed down the pace so as not to drop Pantani and let him win the stage. Pantani did not raise his arms. He knew he owed the victory to a concession. And he was very angry when Armstrong declared that yes, he had let him win because he was a great cyclist who had suffered a lot. He was referring to his disqualification for an excess of red blood cells when he was wearing the maglia rosa in the middle of the 1999 Giro. Pantani let off steam a few days later, with a clear victory on the summit of Courchevel and a crazy ride on the road to Morzine, over 130 kilometres and five passes, which put Armstrong on the ropes. The American suffered the worst crash of all his Tours on the ascent of the Joux Plane, but by then it was Pantani himself who had broken down.

While the battles between Armstrong and Pantani were attracting all the attention, a newcomer arrived at Mont Ventoux in third place, barely twenty-five seconds later: Joseba Beloki.

Then, on the Joux Plane, Beloki left that knocked-out Armstrong behind, consolidated third place overall and thought that the American had saved the yellow jersey that day but that maybe sometime....

That day the possibility occurred to him. And that was already a lot.

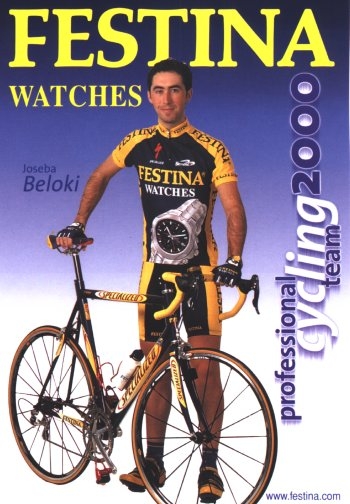

Beloki, born in Lazkao (Vitoria), was making his debut in that 2000 Tour with the mission of being a versatile cyclist in the Festina team. In the first week he had to work for his roommate Marcel Wüst, a German sprinter who won a stage, and in the mountains he had to keep an eye on his two leaders: Christophe Moreau and Ángel Casero.

- Then the race started to put us in our place," says Beloki.

Armstrong used to be in the habit of deciding the Tour on the first day in the mountains. He did so that year on the climb to Hautacam: he gained three minutes on Ullrich and Zülle, and five on Pantani, his main adversaries. The Festina riders responded well: Moreau climbed to third place in the classification and Beloki to sixth.

That day, Armstrong's voracity threatened one of the most dramatic victories of the Basque cyclists in the Tour. Javier Otxoa, from Bizkaia, had escaped with 160 kilometres under the rain, he had dropped his breakaway companions on the Marie-Blanque and the Aubisque, and had reached the foot of Hautacam, exhausted, with a ten and a half minute lead over the favourites. Armstrong was cutting him down by almost a minute per kilometre. With two kilometres to go, he seemed on the verge of catching him. Otxoa pushed on in sheer agony to the finish line and raised his arms with a handful of seconds to spare.

A few months later, a driver hit Javier and his twin brother Ricardo, also a professional cyclist, during a training ride. Ricardo died, Javier spent two months in a coma and was left with irreversible neurological injuries. He returned to cycling and became Paralympic champion at both the Athens and Beijing Games. He died in 2018 from a brain tumour.

- Armstrong and Ullrich were far superior, Moreau and I tried to hold their wheel as long as we could and that was it. We had no other options.

After his magnificent climb of Ventoux, Beloki was third in the standings, one minute ahead of his team-mate Moreau. On the day of Morzine, he took a few more seconds off him and that's how they reached the 58-kilometre time trial in Mulhouse, with 1'44" in Beloki's favour.

I have a very nice memory: Moreau and I hugged each other before the time trial, wished each other good luck and went out to give everything to play for the podium between team-mates.

Moreau was faster but Beloki kept a 30" lead in the overall.

- I don't remember anything about the podium in Paris. I was under a lot of tension on the laps along the Champs Elysées, it was enough to have a puncture, a fall or a cut in the peloton to lose the podium, so I finished the Tour with a lot of anxiety. As soon as I crossed the finish line, the people in charge of the protocol abducted me, they took me here and there, I could hardly be with anyone in the team to celebrate, they took me to the podium and I climbed like an automaton with Armstrong and Ullrich. It should have been an incredible moment, but I was in a daze and it's the podium I remember the least of the three.

Only later, at the celebration dinner with the team, did he start to relax and realise what he had achieved on his debut.

The 2001 comeback

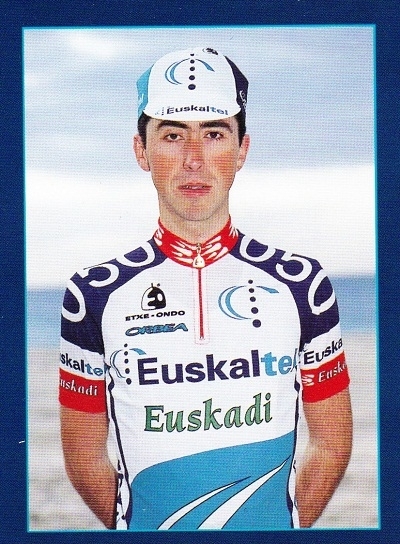

In the following months he confirmed that he had placed himself at the forefront of world cycling. He received a proposal from ONCE to become its leader for the Tour. It was one of the most powerful teams in the peloton and in 2001 it was backing a Basque trident: the veteran Abraham Olano and the new signings Igor González de Galdeano and Joseba Beloki.

- At ONCE, the hierarchies were much more marked. Everyone had their own role and their own programme. I had to focus exclusively on the Tour.

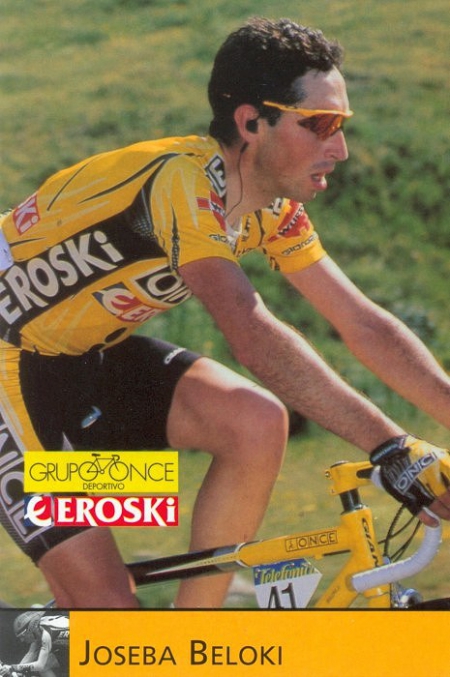

He started with a few races, gradually fine-tuned his form, came second in the Euskal Bizikleta, won the Volta a Catalunya and was in top form at the start of the Tour. In the first week everything went perfectly: he was seventh in the prologue, ONCE came second in a long team time trial, only behind Crédit Agricole, and took more than a minute off the Armstrong and Ullrich squads. Beloki was fifth, ahead of all the favourites, in an unbeatable position to take the yellow jersey on the first mountain stage.

Then the crazy Pontarlier breakaway broke out: fourteen riders escaped, Armstrong's US Postal team was not involved and nobody went for them. They didn't look threatening, almost all of them were already well behind, but they reached the finish with more than half an hour's lead and among them was the Kazakh Andrey Kivilev, a good climber with some prestigious victories, who suddenly found himself thirteen minutes ahead of the favourites.

- I don't think anyone was aware of the seriousness of that breakaway," says Beloki. In the following days, I was convinced that I was going to make up all that lead that Kivilev and the leader François Simon had without any problems, we were taking time off them in the Alps, but Kivilev was holding on much longer than expected. Armstrong and Ullrich overtook him in the Pyrenees, but I was running out of ground...

Beloki came fourth in the final 61-kilometre time trial, 1'20" behind Kivilev. He took 2'08" off Kivilev and thus achieved his second consecutive podium, on the eve of arriving in Paris, by the skin of his teeth.

- We were told that in Pontarlier we calculated the advantage we left to the breakaway. Calculate? We didn't calculate anything. It was a mistake, we let them go. If instead of 36 minutes they had taken 37 minutes, I would have missed out on the podium.

Kivilev died of a skull fracture after crashing in Paris-Nice in 2003. From then on, helmets became compulsory in professional cycling.

Hang on, hang on...

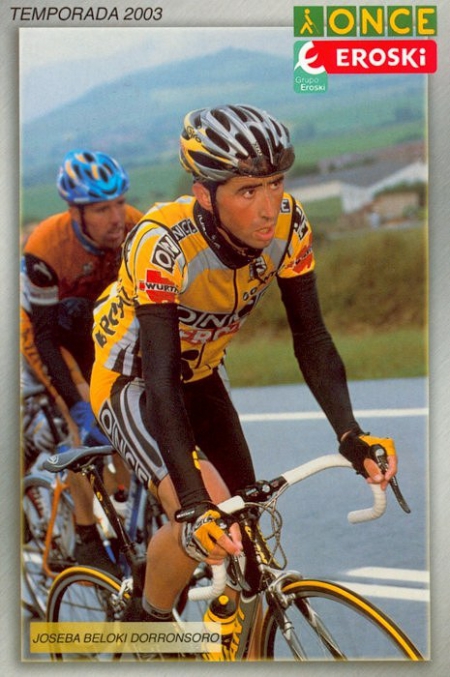

Beloki again came close to the yellow jersey in the first week of the 2002 Tour. He finished ninth in the prologue and the ONCE won the fourth stage.

- It was my best day as a cyclist. The team time trial was the most beloved discipline in the ONCE, we worked hard on it, it motivated us. It was very cool to win in the Tour as a team and to all get on the podium.

Two men from Vitoria led the classification: Igor González de Galdeano was the leader for a week and Beloki was just four seconds behind him. Did you still have the regret of not wearing the yellow jersey for at least one day?

- I wasn't worried at the time. I looked at the classification, I saw that we were all in the team in the top positions and that made me very happy. Then there was a 52-kilometre flat time trial, Igor kept the jersey, Armstrong passed me by a few seconds in the classification, but I already had a good cushion over my opponents for the fight for the podium: Heras, Botero, Mancebo... My final objective was Paris. I wasn't thinking about wearing the yellow jersey one day.

There was one stage where he did fantasise about it: on the first day in the Pyrenees, with the climbs of the Aubisque and La Mongie, the ski resort four kilometres before the Tourmalet.

- Igor and I had recognised the stage. It suited me perfectly, I felt great, and when I saw that Armstrong had his team set a strong pace from Sainte-Marie-de-Campan, instead of attacking from the bottom himself, as he usually did on the first mountain stage... then I thought I had a chance of winning the jersey. Armstrong's team-mate Roberto Heras pulled in the last kilometres and I was left alone with the two of them. It was strange that Armstrong stayed on Heras' wheel almost to the end, so I had my hopes up. I thought I had a chance to leave Armstrong behind. But in the end he took off and blew me away in the last few metres.

The first mountain stage, says Beloki, always put him in his place. And after his third places in 2000 and 2001, it seemed that in 2002 that place was going to be the second step. But the ONCE team stood out for its aggressiveness and its block strategies. They decided to test Armstrong on Mont Ventoux, a mountain where Beloki had always performed well. Mikel Pradera was part of the day's breakaway, to act as a bridge if Beloki managed to distance the American, and José Azevedo attacked three times in the small group of favourites, until he unhooked Heras and left Armstrong with no gregarios.

The moment had arrived: with eight kilometres to go, Azevedo accelerated again and Beloki took advantage of this as a springboard to launch an attack.

Armstrong didn't give him a chance to dream for fifty metres. He jumped on his wheel and finished him off with one of his attacks in a flurry, dancing on the bike and turning the pedals like a pinwheel. Beloki suffered, lost ground, saw Rumsas, Basso and Mancebo overtake him.

- From the Chalet Reynard onwards, it was a very long ride. That day I had to try, I had to test Armstrong, but I ended up falling behind other rivals and put the podium at risk.

Beloki says he learned a lot that day.

- I learned that if you go four pedal strokes too far in the Tour, you end up paying for it. Armstrong was far superior. I could have continued attacking him like that in another couple of stages, people like that, you attack and people love you more, even if you then sink. It would have been nice, but I would have finished fifth or sixth and it would have been interpreted as a step backwards.

Beloki explains that he was racing for something else: to get the best possible place in Paris.

- I was an endurance rider. I hung in there, hung in there, hung in there. Look, when I was a kid I was a sailor, I loved Lejarreta. And I was the first one from the sofa to ask him to attack, I was eager for him to unhook Chioccioli and take the maglia rosa away from him, but I really appreciate that cycling of endurance and of maintaining the suffering every day until the last metre. It wasn't enough for me to attack and then, if it didn't work out, to relax and let myself go.

Getting on the podium of the Tour is very difficult. Beloki recalls that very few cyclists in history have managed to get on the podium three times.

In 2012, after the revelation of his doping system, the UCI stripped Armstrong of his seven Tour victories. And the organisation decided not to award those wins to the runners-up in those years, so Beloki appears as third, third and second in Tours that do not have a first-place finisher.

- The Tour declared Pereiro the winner in 2006, after Landis' disqualification, but I don't know why it didn't do the same in the Armstrong years. Neither Ullrich, nor I, nor anyone else has claimed those victories or those climbs in the classification, because we don't even know what the decision is based on. What makes me sad is that they don't give us explanations.

All out for the best

Beloki was the first to go on the attack on the Alpe d'Huez ramps in 2003. He was a cerebral cyclist, he bet on holding on as long as possible with the frontrunners to get the best position, but he didn't hesitate to go for the big one when he saw a favourable situation. And in that Tour, Armstrong looked more vulnerable than ever. As the stages went by, he was surrounded by a whole cloud of adversaries: Ullrich, Vinokúrov, Basso, Hamilton, Zubeldia, Mayo, Beloki himself...

- That year Armstrong wasn't so strong, he had more rivals than ever and it looked like he might not be able to control us all. It was time to put him to the test.

Beloki opened a gap of fifteen seconds. Behind, Heras did another extraordinary job for his boss Armstrong: he pulled, pulled and pulled, kept the distance, until the American accelerated and caught up with the Basque. But this time, unlike on Mont Ventoux, he was content to stay at his side. In fact, they slackened their pace a little and other riders who were lagging behind caught up with them. In those moments of doubt and vigilance, with seven kilometres to go, Iban Mayo let loose a whiplash, flew to the summit of Alpe d'Huez and signed a historic victory for the Euskaltel team. He obtained a striking difference: more than two minutes.

That day Armstrong wore yellow with two Basques on his heels: second Beloki, 40" behind; third Mayo, 1'12" behind. Vinokurov, Hamilton, Ullrich and Basso lurked a couple of minutes behind. If one didn't attack him, another would attack him. Armstrong's team was finding it hard to put out all the fires, a fire could get out of control at any moment.

The next day was a complicated stage on the road to Gap, with two big passes such as Lautaret and Izoard in the first part, and a couple of modest climbs at the end. ONCE decided to try again: Jaksche, who was just over three minutes behind in the standings, slipped into a breakaway that reached more than six minutes, forcing the US Postal to empty itself in pursuit. Armstrong ran out of companions on the penultimate, second-category pass, still far from the finish line. And Beloki attacked on the final climb of La Rochette.

- I attacked going up and Armstrong followed me, so I attacked again on the descent. I wasn't very good going downhill, but it was the moment to make Armstrong tense up, to see if he preferred to be cautious and let me go... I went down and what you all know happened.

What we will always remember happened: on a stretch of asphalt melted by the heat, Beloki's tubular came off, he lost control of the bike on his way down at full speed and fell flat. Armstrong dodged it by the skin of his teeth, went off the road, rattled downhill through a cereal field and miraculously emerged, with no falls or punctures, onto a lower stretch of road. The American got back on the road just as his rivals arrived and continued pedalling for the fifth of his seven Tours. Beloki was left on the ground like a disjointed puppet, screaming in pain in front of the cameras, with fractures to his femur, elbow and wrist.

Beloki is not hurt by the lost opportunity in that Tour, because he accepts risks and accidents as part of the game, but he is hurt that his sporting career was cut short so abruptly. He never recovered his level. And he vindicates the value of that scene, beyond the impression it left on the memory of cycling because of the terrible blow: it was the moment of a maximum gamble, the moment of his plenitude.

- That was the end of it all, the end of trying.

Author: Ander Izagirre