INDURAIN FLIES FROM SAN SEBASTIÁN TO PAMPLONA

author: Ander Izagirre,

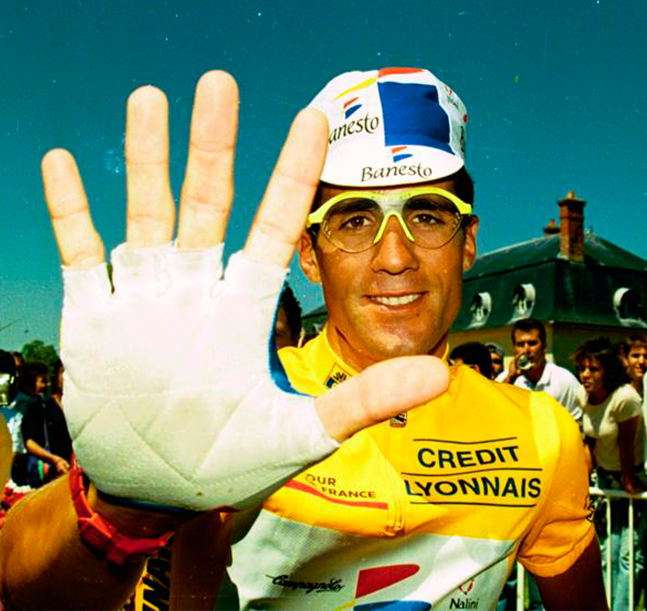

Miguel Indurain skirted the bay of La Concha at 55 km/h, wearing the yellow jersey, coupled with his time trial bike. It was the dream image, the best gift that the Tour could bring to the Basque fans: the launch of their idol from the Alderdi Eder ramp for his second victory in the French Tour. Indurain flew off, headed inland, rode down a long avenue, turned, returned along the same avenue, crossed La Concha again like a missile and rode through the centre of San Sebastian leaving a yellow trail amidst the roar of tens of thousands of fans. In that eight-kilometre prologue of the 1992 Tour, Indurain was the last rider to cross the finish line and the one who set the best time: 9'22", at 51.246 km/h on average.

He beat specialists such as Zülle, Marie and Nijdam by a whisker. Bugno lost 12"; Lemond and Breukink, 14"; Chiappucci, 30"... On the podium, cheered by the crowd, Indurain shone in yellow like a solar divinity perched on top of a pyramid. The best thing is that he never took our veneration too seriously. While the international journalists would give him nicknames like someone scattering incense (Miguelón, the Extraterrestrial, the Giant Navarro, Le Roi Miguel, Big Mig), his ultimate expression of pride after a feat was limited to this phrase:

-We have been there.

The pyramid

The base of that pyramid was built in the 1980s. Television broadcast live for the first time the 1983 Vuelta a España, a legendary edition with the young Marino Lejarreta, Julián Gorospe and Alberto Fernández climbing on the beard of the almighty Bernard Hinault, who struggled a thousand times and won with a ride through the mountains of Ávila.

That same year, the Reynolds team from Navarre presented itself as a team of rookies in the Tour and almost pulled off a surprise: Arroyo won the time trial up the Puy de Dôme and finished second on the podium in Paris, Delgado put on an exhibition in the mountains and came close to the yellow jersey until he had a massive breakdown. Indurain made his debut in this team without complexes in 1985. He came second in the prologue of the Vuelta a España and two days later he wore the yellow jersey: at the age of 20, he was the youngest leader in the history of the Vuelta. The Navarrese rider appeared at a moment of hatching.

The exploits of the new generation of cyclists and the televised broadcasts attracted many sponsors. In the Basque Country, the number of teams increased, budgets multiplied and resources improved. Legendary squads such as Fagor and Kas returned to the peloton with ambitious projects; others such as Orbea, BH or Zahor emerged; Reynolds was born in Irurtzun and arrived in yellow in Paris for the first time with Delgado in 1988. More youngsters than ever competed in the lower categories, the professional calendar was full of races (Tour of the Basque Country, Euskal Bizikleta, San Sebastian Classic, Urkiola Climb, Getxo Circuit, Ordizia Classic, Amorebieta Spring Classic, Estella Grand Prix...) and fans flocked both to watch the local races and to camp in the Pyrenees while waiting for the Tour.

From this broad base, top-level international cyclists grew, like the top rungs of the pyramid. The main Basque stars of the 1980s took part in their stage of the Tour: Pello Ruiz Cabestany's (Orbea) agonising victory with the peloton on his heels in 1986; Julián Gorospe's (Reynolds) gallop over four passes that same year; Fede Etxabe's fabulous triumph on Alpe d'Huez in 1987, after scattering his twenty breakaway companions along the way; Lejarreta's victorious attack from the group of favourites on the ascent to Causse Noir in 1990... On that day, the runner-up was precisely Miguel Indurain, who the previous year had already won a Pyrenean stage in Cauterets and then went on to win another in Luz Ardiden. The high mountain triumphs of the Villavese, who was only considered a time trialist, were increasingly powerful announcements of the advent of his era.

On 19 July 1991, Greg Lemond attacked halfway up the Tourmalet. Indurain, impassive and constant, set a strong pace in the small group of favourites and kept it up kilometre after kilometre, until he caught the American triple winner of the Tour. On the last bend, Lemond dropped a few metres. It didn't seem serious, because they were already cresting the pass and he could make up the deficit straight away, but at that moment all the experience that Indurain had accumulated in the Tour since 1985 came to the fore. He knew that an exhausted cyclist is a cyclist with no reflexes, therefore he put on the big chainring, got up on the saddle and sprinted downhill, at eighty, ninety, a hundred per hour, flying on the straights and tracing the bends to the millimetre. Indurain knew how to patiently climb a mountain pass out of category, he knew how to wait and watch, he knew how to recognise the exact moment when something was breaking inside a rival, he knew how to take that rival to the limit of suffering and then finish him off. He knew the curves of the Tourmalet by heart. He was left alone and flew for his first Tour. At the end of the descent, his director José Miguel Echávarri ordered him to wait for Chiappucci, who was close behind him, and together they rode the rest of the stage through the Aspin and the final climb to Val Louron. They widened the gap to their pursuers: Bugno reached a minute and a half, Fignon three minutes, Mottet four, Lemond seven, Delgado fourteen... Two hundred metres from the finish, Indurain made a gesture with his arm to signal Chiappucci to pass. The Italian won the queen stage and the rider from Navarre wore the yellow jersey until Paris.

This is how he presented himself in San Sebastian, at the start of the 1992 Tour, dressed in yellow at the top of the pyramid.

-I'm not superior to anyone," he said after winning the prologue and renewing his lead. But now I'm ahead and the others will have to attack me.

They attacked him immediately.

Zülle's slipper

Manolo Saiz, director of the ONCE, was still ruminating on the frustration of the previous day. He came to the Tour with the loss of his three strongest riders: Laurent Jalabert, Melchor Mauri and Marino Lejarreta, who had suffered a very serious fall in the Clásica de Amorebieta, close to his home. Saiz believed that a victory for the young Zülle in the San Sebastian prologue and the resulting yellow jersey could save the Tour for ONCE, but the Swiss rider was two seconds behind.

-We were very careful in the prologue, we analysed the wind and temperature to decide when our riders should start and the most suitable tyres, Etxeondo prepared special aerodynamic overalls for us... Then Indurain would arrive and beat us by a couple of seconds," Saiz says, with a half-smile.

Saiz worked hard on his strategy, taking advantage of any opportunity to spring a surprise. At the start of the first stage of the 1992 Tour, he climbed the Orio pass, a kilometre-and-a-half-long tack, and then descended to Zarautz, where there was a flying finish with bonus seconds and points for the green jersey. Before the start of the stage, Saiz spoke to Mario Cipollini.

-Cipollini was the leader of the sprinters, his team was the one that pulled or didn't pull to chase the escapees. I told him: "Look, Mario, Zülle is going to attack on this climb in Orio to take the bonus in Zarautz. I ask you not to go for him. And I also ask you another favour: I don't think Indurain will sprint for the second place bonus, but if you can come second, just in case...".

Zülle gained six seconds, became virtual leader... and in the middle of the stage he dropped out of the peloton.

-He started to have problems with a shoe," says Saiz. In the end, his team-mate Xabier Aldanondo had to give him one on the fly and we had to chase the peloton before Jaizkibel. On the climb there was a battle between the favourites, Zülle stayed behind, we chased again to get into the lead, then to catch three escapees who were a minute behind... What an ordeal.

In Jaizkibel Chioccioli attacked and was followed by only eight riders: Chiappucci, Bugno, Indurain, Breukink, Hampsten, Leblanc, Roche and Lelli. Lemond, Fignon, Mottet and Delgado, the dominators of the 1980s, were not there. The generational change was evident. In the end they all regrouped, Dominique Arnould won with a last-minute attack on the Zurriola finish line and Zülle took the yellow jersey.

Murguialday's adventure

Another rising star of the 1990s attacked at the start of the next stage, the very long San Sebastian-Pau. He was a 22-year-old French lad, recruited four days before the start of the Tour to replace a casualty, by the name of Richard Virenque. He escaped on the climb to Aritxulegi, 230 kilometres from the finish line. On the way to Baztan, he was joined by two other cyclists: his teammate Dante Rezze and Javier Murguialday from Alava. They climbed Izpegi and passed Baigorri with a 22-minute lead. After the very hard Marie-Blanque, with Rezze already dropped, Virenque and Murguialday made a pact: leadership for the Frenchman, victory for the Spaniard, who thus continued the tradition of Basque cyclists who won stages of the Tour on Basque soil, such as Nazabal in Vitoria and Lasa in Biarritz.

Indurain went on the attack on the Marie-Blanque with Chiappucci, Bugno and Mottet, gained a few seconds in Pau over the other favourites and came out of those three Basque stages catapulted towards his five consecutive Tours. A few days later, he gave the most overwhelming display in the speciality that he had dominated flawlessly for five years. In the Luxembourg time trial, 65 kilometres long, he pulled out a stratospheric gap on his rivals: he got 3'41" on Bugno, who had given up the Giro to attack the Tour and who after this blow never lifted his head again ("in the peloton we are 179 riders and an alien", he said that day); more than four minutes on Lemond, Roche and Zülle; five minutes on Delgado; five and a half minutes on Chiappucci. Indurain overtook three riders on the course, the last of them Fignon, who had set off six minutes earlier and couldn't believe it: "I've been passed by a missile".

In this Tour, Indurain also resisted the most brutal attack in the mountains, the only one that made him falter in five years. Chiappucci escaped in the Alps with two hundred kilometres and five mountain passes to go, he arrived at the finish line in Sestrieres converted into a wreck, after relieving himself, covered in snot and drool, and in the hotel they injected him with a drip of serum to help him recover. But it forced Indurain to pedal for hours on the edge of his strength and caused him to suffer a very dangerous fainting spell. The Navarrese rider melted, and if he only gave up 1'45" it was because he had a breakdown in the last two kilometres. If his reserves had run out a little earlier, Diablo Chiappucci would have changed the history of the Tour.

"Without your imposing presence, I know that I would never have reached my best," Chiappucci wrote to Indurain in his farewell letter in 1997. "I was admired for my great escapes, but I would never have undertaken them if you hadn't forced me to. To have even the slightest chance of destabilising you, there weren't a thousand methods: I had to attack you from a long way off. That's why I did it, and I took a liking to that way of running. That's how I won the hearts of the fans, thanks to you, my rival, the best of my rivals.”

Indurain also dominated the Tours of '93, '94 and '95 with the same method. He destroyed his rivals in the long time trials of that period, climbed the mountains with the best climbers, sometimes faster than them, and gave up the stage wins so that his rivals would be satisfied with those consolation prizes. When someone tried to spoil the formula for him, like the ONCE team with their attacks and the distant breakaways of Zülle in 1995, Indurain also responded with surprises: he started from the peloton on the Liège climbs, overtook all his adversaries, took a minute off them and above all ate up their morale. The next day he widened the gap by beating the best specialists (Riis, Berzin, Rominger...) in a time trial; and the following day he crushed the best climbers (Pantani, Virenque, Tonkov, Chiappucci...) on the climb to La Plagne. Once the spectacular collective attack by ONCE on the road to Mende was saved, he dedicated himself to keeping an eye on the wheels of his adversaries and letting them share out the stages. Peace for all, five Tours for Indurain.

Farewell in Pamplona

In the first half of 1996, the Navarrese won the Tour of Alentejo, the Tour of Asturias, the Euskal Bizikleta and the Dauphiné Libéré, so he arrived in an apparently splendid state of form for the conquest of the impossible: the sixth victory in the Tour, the Holy Grail of cycling, the endeavour in which all the five-time champions (Anquetil, Merckx, Hinault) had fallen. That road to glory passed, moreover, through his own front door. The Tour prepared the last mountain stage with a finish in Pamplona. And it became a cruel trap.

Indurain arrived defeated on that day. He had collapsed in the Alps, in a day of cold, rain and sudden heat, dehydrated, disembowelled, buried by an avalanche of four minutes in four kilometres in Les Arcs. He tried to turn it around in the time trials and in the mountains, but it became clear that it wasn't just a bad day: he was always four, six, eight riders ahead of him. The stage between Argelès-Gazost and Pamplona was a brutal 262 kilometres with four terrible passes in the first part (Aubisque, Marie-Blanque, Soudet and Larrau), four fangs that crushed Indurain, and then a 100-kilometre via crucis through the Pyrenean valleys of Navarre. He fell behind in Larrau and lost eight minutes in Pamplona.

The tribute was still a tribute. Not to the winner of a sixth Tour, but to a cyclist who won people over with his simplicity and elegance as much as with his string of five victories. Indurain crossed half of Navarre through a corridor of spectators who applauded him with emotion. As he passed through Villava, his home town, he turned to greet his parents and his wife, who was carrying his son Miguel in her arms, with a smile on her face. And in Pamplona he was asked to stand on the podium. The yellow jersey Bjarne Riis handed him a bouquet of flowers and raised his arm in the air, Indurain waved a little hastily, threw the flowers into the crowd and left immediately.

Author: Ander Izagirre