THE FIRST DEAD MAN OF THE TOUR, PACO CEPEDA

author: Ander Izagirre,

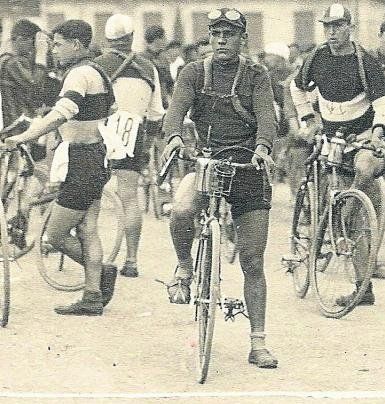

Five riders were descending the gorge of La Romanche. They formed one of the many small groups that had dispersed on the ascent of the Galibier, during the seventh stage of the 1935 Tour, and were flying in relays to reach Grenoble with as little delay as possible. Among them was Francisco Cepeda, a native of Sopuerta. Just past the village of Rioupéroux, Cepeda went to the ground on a bend and knocked Adriano Vignoli over. The Italian retired with a broken collarbone. The Basque rider got back on his bike and resumed the ride, but collapsed a few metres further on. The Spanish team car took him to the hospital in Grenoble, where he was diagnosed with a fractured skull. He was trephined to reduce the pressure of the haematoma. But he died three days later, at the age of 29.

Cepeda smiles in the portraits with his combed slicked hair, broad forehead, expressive nose, prominent jaw, exuding confidence. He worked as a justice of the peace. He earned his living by settling small municipal disputes, but only really enjoyed it when he escaped from the office on his bicycle. First, to visit his girlfriend and return: sixty kilometres that served as training. Then to enter races and win many of them, the Getxo Circuit, the Easter Grand Prix, the bronze medal in the Spanish championship, until he took on the great adventure: the 1930 Tour. He was the first Basque to finish the French race in 27th position. And he never managed to finish it again: in 1931, he retired ill almost at the end; in 1933 he arrived out of control in the first stage, like Jean-Baptiste Intzegarai from Labortano; then he retired from cycling, but in the office he could not resist the itching and joined the powerful Orbea team again. In 1935, he took part in the first ever Vuelta a España and came 17th. It was not enough for him to be included in the Spanish national team for the Tour, but he had no doubts: he signed up as an independent cyclist, with his father, a businessman who preferred to see him in his post as a judge, with the comfort of the office and the guaranteed good salary, and not spending misery in that wild race. Cepeda left his chair, got into the saddle and threw himself into that passion that devoured him. And so did it.

The circumstances of the accident turned out to be very confusing and all kinds of versions circulated, because that Tour had already been plagued by far-fetched episodes. It was reported that Cepeda had been run over by a car belonging to the organisation. In reality, the car had hit other riders at the start of the stage: Gustaf Danneels, the Belgian champion, and Antonin Magne, winner of two Tours, retired due to injuries. The winner that day in Grenoble, Francesco Camusso, would also retire a few days later after being hit by a team car.

Several witnesses testified that Cepeda suddenly lost control of his bike. The court case was closed six months later without explanation, but one main hypothesis remained: Cepeda's tubular had come loose from the rim.

It was an uncomfortable hypothesis for the Tour organisers. On the second stage of that edition, the four riders in the breakaway got punctures one after the other. The favourite Archambaud also punctured six times and lost half an hour. Giuseppe Martano, second in the previous Tour, punctured so many times that he retired in despair. It was not the traditional sowing of nails with which some spectators caused punctures (except for the cyclist from their village, who was told which side of the road he had to pedal on to escape from this). That year, for the first time, the wheels provided by the organisers had duraluminium rims instead of wooden rims. On hot days, with the metal on fire, the tubulars burst. Or came loose, because the glue melted. It happened on hot days or on long descents, like the Galibier, when the friction of the brake pads overheated the rims. The organisers tiptoed around the issue, which could have cost them a legal sentence, but the punctures, tubular leaks and consequent crashes proliferated so much that three days after the accident, just when Cepeda's death became known, they replaced the old wooden rims.

The Biscayan was the first cyclist to die in the middle of the Tour, although there was another who died on a rest day during the 1910 edition. Adolphe Hélière, a boy who raced as an isolé (isolated, without a team), arrived exhausted at the finish line in Nice after a 345-kilometre stage, nine and a half hours behind the winner. He slept on the beach, as many isolés did, because they preferred to save money on hotels and spend it on food: fuel for the race. The next day, Hélière took a big meal, a dip in the sea and suffered from thermal shock. They pulled him out onto the sand, tried to revive him, where he died. He was 19 years old and, according to his companions, he was looking forward to passing through Rennes, his home town, a few stages later.

In addition to Cepeda, two other cyclists died during the Tour: Italy's Fabio Casartelli, who hit his head on a concrete wall on the descent of the Portet d'Aspet in 1995, and Britain's Tom Simpson, who collapsed due to a mix of heat, alcohol and amphetamines during the 1967 ascent of Mont Ventoux. The televised images of Simpson zigzagging on his bike seconds before collapsing, shocked the cycling world and changed its rules. The following year, the Tour introduced doping controls for the very first time.

The cyclist from San Sebastian, Ramón Mendiburu, witnessed to that episode on the Ventoux.

- That day on the way out of Marseille it was sunny as hell. I'll never forget Tom Simpson collecting water from a ditch with his cap and pouring it over his head. I thought: "If you're already roasted now, what will you be like in 200 kilometres...". I also remember that in the middle of the race, Jesús Aranzábal put his head in a water trough, and came out with all the moss hanging out of his ears... and with two bottles of champagne that someone had left to cool down. I climbed the Ventoux in a small group with Stablinski. With a couple of kilometres to go to the top, on that scree, we saw a crowd of people on the side of the road around a cyclist lying on the ground. Doctor Dumas was giving him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Stablinski asked: “Qui est-ce?”. “C’est Tom, c’est Tom!”.

Cycling is a game between joy and anguish. Like no other sport, it is preceded by announcements of urgency: motorbikes howling sirens, cars honking, helicopters buzzing. The spectator waits anxiously on the sidelines. Something is going to happen. And it happens, a swift swarm, burst of colours, pyrotechnics. The spectator applauds with the happiness of a child but also sees, very closely, disturbing scenes: grimaces of suffering, noses dripping with sweat, lost looks, a terrible fall like the one of Cepeda. The battle is invented but the pain is real. Cycling does not fascinate because it flirts with death, but because it plays to the limit with that strange human capacity to accept risk and suffering. And because it does not ignore - no one should ignore it - that one centimetre further on there is no remedy.