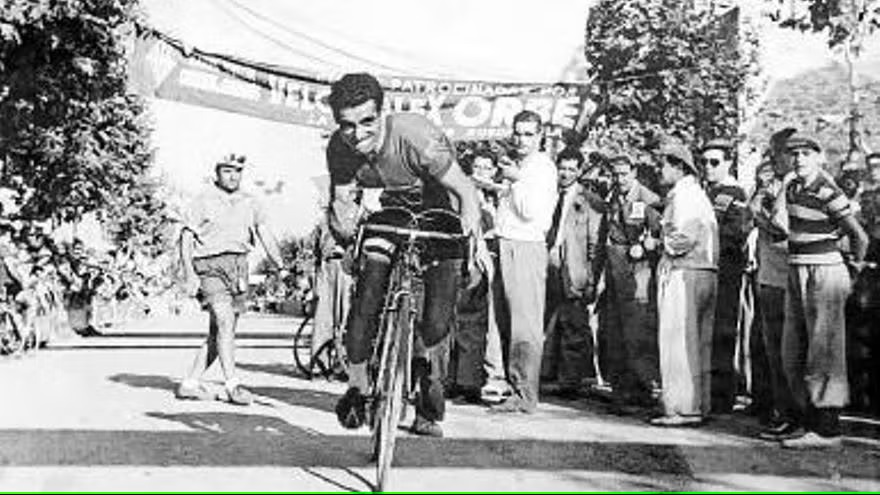

LOROÑO CROUCHES DOWN TO REACH THE SUMMIT

author: Ander Izagirre,

Jesús Loroño heard the ringing of a bell and saw the train barrier coming down. He broke away from the peloton, ducked under the barrier at the last moment and continued towards the first ramps of the Aubisque. Ahead of him, three riders: Drei, Huber and Darrigade, three minutes ahead. Behind, the peloton had to wait for the train to pass.

The barrier was lucky for Loroño but also a reward for his trepidation: he rode at the head of the peloton, alert to any movement, ready to launch an attack on the Aubisque because he was convinced that it was his day.

His day (13 July 1953, the Pau-Cauterets stage) to emerge from international anonymity.

He would be very good in the low Basque mountains, they said of Loroño, has won the Arantzazu and Arrate climbs, and also the Naranco in Asturias, but you take him out of his farmhouse in Larrabetzu and he shrinks. A few years ago, he came tenth in the Vuelta a España, yes, but with a weak participation and an hour behind the leader. In 1953, when the Spanish coach Mariano Cañardo announced that he would take him to the Giro d'Italia, Loroño replied that he didn't want to. Where was he going with those terrible mountains, just the first time the Stelvio was climbed, with those figures, Coppi, Bartali, Koblet: nowhere. Cañardo threatened never to call him back for any more international races, so Loroño completed the Giro with dignity, finishing 43rd, but his name did not appear in any chronicle. At least, he earned a place to make his debut in the Tour de France. Loroño was not a kid, he was already 27 years old. And the coach Cañardo made his role clear to him: the Spanish team would have four leaders, Gelabert, Masip, Serra and Trobat, and six domestiques who would have to give them their wheels in case of a puncture, stop to get water for them at the springs and wait for them if they fell behind. Loroño looked strong and asked for freedom on some of the mountain stages. "No way", Cañardo told him, "you came to the Tour to help".

Loroño played the role of a domestique in the first nine stages and reached the Pyrenees in the penultimate position in the general classification. His sacrifices had not been of much use either, the leaders of the Spanish team had accumulated a huge delay, so at the start in Pau it was clear to him that his turn had come: a short stage, just 103 kilometres long, with the ascent of the Aubisque, the Soulor climb and the high finish in Cauterets, ideal for him. That's why he cycled in the lead in the first kilometres, that's why he saw how the train barrier was coming down, that's why he shot out of the gate to sneak in and leave the peloton in the dust.

Loroño opened a gap thanks to his picaresque, but that day he was flying. The photos of the Aubisque show him leaning on the front wheel with a grimace of aggressiveness and suffering, his jaw fierce, his nose a prow, his cap tilted to one side, his tubulars rolled up on his back, a few mouthfuls peeping out of his chest pockets and two metal bottles with cork stoppers fixed to the handlebars. He was a tall cyclist, against the tradition of the flea-like climbers who leapt up the gravel slopes. Loroño climbed powerfully, he moved development. He immediately overtook the escapees. By Eaux-Bonnes, where the hardest ramps begin, he was two and a half minutes ahead of the peloton. There, the Swiss Hugo Koblet, winner of the Giro and the Tour, and top candidate to wear the yellow jersey again in Paris, attacked with a fury that baffled his rivals. "He went out like a rocket, we were amazed", said Italian Gino Bartali, "it was a suicidal attack". At the start Koblet cut Loroño's lead but was unable to keep up the pace. The Basque rider crossed the Aubisque in first position, five and a half minutes ahead of Koblet and six minutes ahead of a small group of favourites. Koblet, who had lost ground on the Soulor, was left behind by his rivals, and then set off downhill to make up ground. He skidded on a bend, hit a pylon and plunged into a ravine. He was taken to hospital with his head bandaged like the one of a mummy.

Loroño held the advantage in the valley and the gentle climb up to Cauterets, against the constellation of stars chasing him: Robic, Astrua, Bobet, Bartali... He won with six minutes. Cañardo embraced him at the finish: "You saved us, Jesus". And the French newspapers spoke of Loroño, the surprise of the Aubisque. But he was not satisfied: in the following stage he crossed the Tourmalet, the Aspin and the Peyresourde among the first ones, to score points in the mountain prize. The king of that classification was Jean Robic, the diminutive Breton climber who, when he took the lead on the Tourmalet, picked up a jerrycan full of lead to descend as fast as his bigger rivals. And down he went, down he went so fast that he fell twice because he couldn't control such a heavy bike. Even so, he also topped the next two passes, won the stage in Luchon and took the lead. But a couple of days later he crashed again on a descent, lost 38 minutes and eventually retired with a bruised body. Robic, winner of the 1947 Tour, wore a ring with the Breton inscription Kenbeo kenmaro, "life or death". In the course of his career, he fractured his left wrist, both hands, his nose, his left collarbone, his right shoulder blade, his femur; he split open an eyebrow and suffered the displacement of four vertebrae, he split his skull twice and had it reinforced with a steel plate. That's why he always raced with a leather pad. He was Robic trompe-la-mort, the death cheat.

When Robic left the throne of the mountains vacant, Loroño fought to occupy it. In the queen stage of the Alpes, Louison Bobet launched an eighty-kilometre ride to win the first of his three Tours, and the only one who dared to jump with him was Loroño. He held his own on the col of Vars, fell off the pace on the descent but was still able to take third place on the Izoard and score the points needed to become the first Basque king of the mountains. The climber of the small climbs next to the farmhouse had established himself in the Pyrenees and the Alps against the best cyclists in the world.

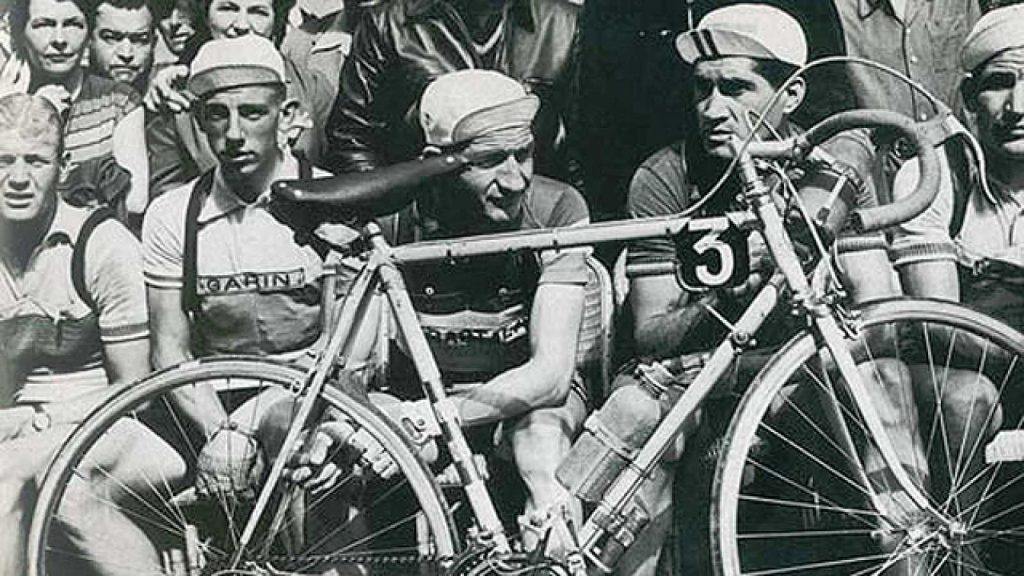

The maturity of Loroño, the first great idol of the Basque fans, coincided with the emergence of Federico Martín Bahamontes. The Toledan cyclist won the mountain prize in the next Tour, in 1954, and from then on, they both claimed the captaincy of the Spanish national team in the grand tours. It was an explosive rivalry. In the 1956 Vuelta a España, Loroño attacked in the last stage, Vitoria-Bilbao, to make up the 43 seconds that the Italian Conterno was leading him. He went over the Sollube pass with a minute and a half advantage, close to the final victory of the Vuelta, but he got a puncture on the descent and was caught at the gates of Bilbao. He was later told that Conterno had joined forces with several Belgian riders to push him on the climb. That was grounds for expulsion, but the judges simply gave the Italian a 30-second penalty: Loroño was 13 seconds off the yellow jersey. And his fury boiled over when the press showed a scandalous photo: Conterno was pedalling clinging to Bahamontes, who was towing him with all his might to prevent Loroño, his team-mate and fierce enemy, from winning the Vuelta.

Loroño took his revenge the following year, when he won the 1957 Vuelta ahead of Bahamontes. He also finished fifth in the Tour, while the Toledan retired in one of his most famous escapes. On the eighth stage, Loroño was part of a large breakaway that reached the finish line 18 minutes ahead. The next day, Bahamontes claimed that his arm hurt from a calcium injection given to him by the coach Luis Puig, got off his bike and laid down among some families having a picnic on the grass while they watched the Tour. His domestiques Morales and Ferraz tried to convince him to continue but Bahamontes refused. No and no. They mentionned his wife: "Do it for Fermina, Fede". "No." "Do it for Spain. "."No." "Do it for Franco!". "No!". Bahamontes climbed into the broom wagon and returned home amid a wave of criticism from colleagues, directors and journalists.

But Bahamontes was very much Bahamontes. In 1958 he faced Loroño in the Vuelta (the Spaniard was sixth and won the mountains, the Biscayan was eighth and won a stage) and in the Giro (the Toledan cyclist won a stage and finished seventeenth, the Biscayan was seventh). For the Tour, the coach Dalmacio Langarica, also from Bizkaia, left Loroño at home and took Bahamontes as leader: he won two stages and the mountains prize. So in the 1959 Tour, Langarica saw it clearly: this time he would take Loroño, yes, but as Bahamontes's domestique. Loroño asked for freedom in the first mountain stages, to see which of the two was stronger, but Langarica told him to forget it. "Then I don't want to go". "Then you're not going".

Basque fans reacted furiously against Langarica. They criticised him publicly in the newspapers and sent him anonymous letters with threats, they smashed the window of his bicycle shop in Bilbao, they insulted his wife in the street. The facts proved him right: Bahamontes won the 1959 Tour.

Loroño, now 33 years old, had to swallow that bitter pill. He didn't shine again, but his sparkle on the Aubisque lit up the first mass enthusiasm for a Basque cyclist in the Tour.

Author: Ander Izagirre