JOANE SOMARRIBA WINS THREE TOURS

author: Ander Izagirre,

It is difficult to climb the Tourmalet in two such different ways.

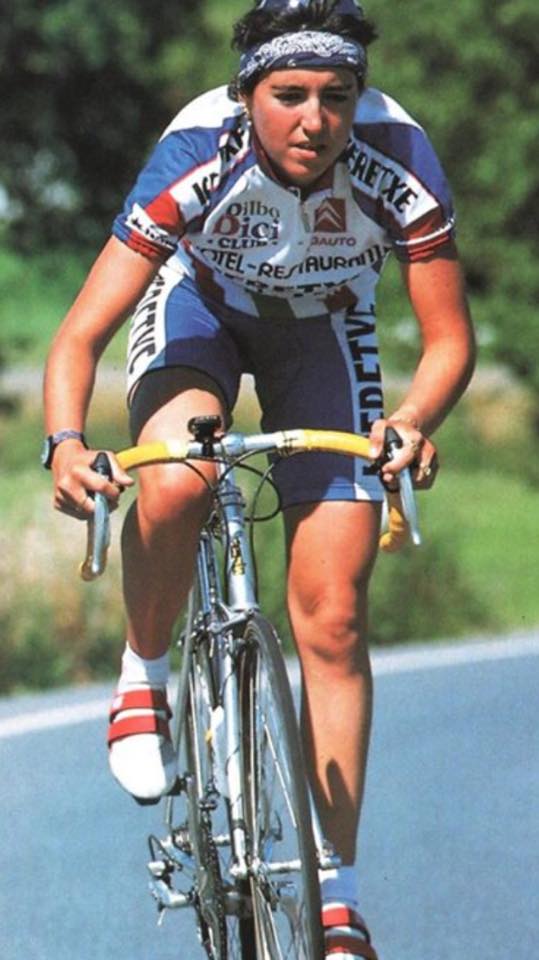

In 1995, Joane Somarriba climbed it at the age of 22 in her first Tour de France, suffering in the last positions, emptied out, struggling to reach the finish line without taking her foot off the ground. Then, came the Alps, the stage with two colossal mountains such as the Madeleine and the Glandon. The Biscayan cyclist described that experience as " a torture", she lost almost one hour to the winner Luperini and promised herself never to return to the damned Tour.

One detail: she did not retire.

A few years earlier, Somarriba had been through an ordeal with a serious back injury that had left her in a wheelchair and it seemed that she would never be able to compete again. She worked hard at rehabilitation, showed extraordinary willpower and got back on the bike. She got used to back pain throughout her cycling career. Despite so much suffering, in that first Tour in 1995 she pushed herself a little more and a little more until she finished it. She reached Paris. And she was curious enough to go to the podium ceremony on the Champs Elysées: she saw Fabiana Luperini, radiant with the yellow jersey, the trophy and the flowers, escorted by the legendary multi-champion Jeannie Longo and the Swiss Luzia Zberg.

Then she changed her mind: "I want to be a winner too. I have to train a lot more.

She wanted to win races. The possibility of standing on the podium in Paris didn't even occur to her.

But five years later, in the 2000 Tour, Somarriba climbed the Tourmalet in a state of grace. That year she had already won the Emakumeen Bira and her second Giro d'Italia. She came to France to help her Lithuanian team-mate Edita Pucinskaite, already a Tour and World Cup winner. In the fourth stage, the two Alfa Lum team riders had escaped together and Pucinskaite had handed the victory to Somarriba. In the fifth stage, in a time trial where team strategies were no longer valid, Somarriba won by a good margin. She looked the stronger of the two, but was still willing to work for the Lithuanian. In fact, in the stage that ended at the top of the Tourmalet, Somarriba obeyed the team's orders and set a very strong pace to punish her rivals. She dropped them all. In the lead, Somarriba and Pucinskaite were alone again, the Lithuanian lost a few metres and the little dance of controversy began.

As Somarriba was in the lead, the version circulated that the director of Alfa Lum ordered her to wait for her team-mate. The Biscayan herself denied this version: "Pucinskaite told me to go away, that she couldn't follow me, but I was the one who decided to lift my foot a little to wait for her. I had already won two stages and I thought it was good for her to take the Tourmalet stage". That's how Somarriba climbed the Tourmalet: leading the Tour, waiting for her team-mate.

"I've never felt so powerful on a bike," she said.

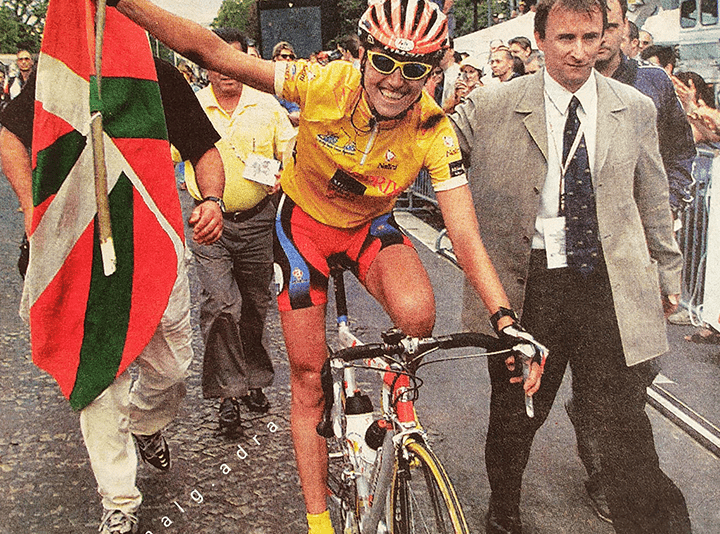

Pucinskaite won the stage of the Tourmalet and Somarriba wore the yellow jersey for the first time in a dream setting for any rider, on that pass at an altitude of 2,115 metres in the heart of the Pyrenees and the history of cycling.

What she did not imagine was that the controversy would grow in the following days. Pucinskaite wanted Somarriba to lose time on purpose to give her the yellow jersey. And then Somarriba stood up: she had come to the Tour to help the Lithuanian, yes, and she had done so in several stages, even slowing down on the Tourmalet to win the yellow jersey, so it was not a question of offering her a Tour de France just for the sake of it. Pucinskaite got angry, got into a row, went on the attack on the following days and the team experienced some very tense days. There were still the Alps, the second time trial and the last mountain stage in the Vosges, a lot of work to do to overcome rivals who were only two or three minutes behind them, and a fight between the two outstanding leaders of the Alfa Lum could ruin the Tour for them. The director brought the two together to establish that at that moment Somarriba had the jersey, she was the strongest and they had to work for her.

On the ninth stage, the Biscayan rider fell. She saved the maillot, but had to have three stitches in her elbow and was in pain in the 26-kilometre time trial. Even so, she finished second, just 14 seconds behind Zabirova, and once again pulled ahead of her team-mate and rival Pucinskaite. Then she exploded in front of the microphones: "When we reached the Tourmalet, Edita told me that I deserved to win the Tour. Since then she has declared war on me every day". Somarriba responded to his rivals' attacks on the last mountain stage in the Vosges. After the Tour, she spoke with Pucinskaite and they reconciled, and since then she has taken the heat off the matter, but she has never forgotten those who lent her a hand in those difficult days: "We went through some very tense moments, but my team-mates always supported me and that gave me a lot of peace of mind".

On 20 August 2000, she walked to the same podium on the Champs Elysées that she had approached in 1995, but this time it was not to admire the champion from below, but to climb the steps to the top and receive the yellow jersey.

IN YELLOW FROM BILBAO TO GERNIKA

The organising company of the Tour de France ran women's editions of the race between 1984 and 1989. When it stopped doing so, it did not allow other organisers to use that name. So the Tour de France won three times by Joane Somarriba was officially called Grande Boucle Féminine Internationale. In any case, it was a sporting equivalent of the Tour: a fourteen-stage race through France, the longest and hardest on the women's calendar, with the best international stars taking part.

So in an official sense you couldn't say, but in a sporting sense you could: the Tour also left Bilbao in 2001, in its women's version. The first stage was held on Sunday 5 August, with two sectors: a ten-kilometre morning time trial through the streets of Bilbao and a 107-kilometre online stage in the afternoon between Bilbao and Gernika, Joane Somarriba's home town (although she later lived in Sopela).

For Somarriba, these were the most exciting days of her sporting career. As soon as she knew that the Tour would take place in her landscapes, the roads where she trained every day, she made that day the main objective of her season. In 2001, she raced some preparation races, took the Giro as a training (she finished fifth) and came to Bilbao in splendid form, with all her voracity and all her enthusiasm.

Somarriba started last in the time trial, with the number one bib and the yellow jersey. She launched herself off the ramp, sprinted down the Gran Vía to the roar of the crowd, got on her bike, flew through the streets of Bilbao, clocked much better times than her rivals for victory in Paris, and even doubled Desbouys, the fourth-placed rider from the previous year, who had started a minute earlier. The problem was Judith Arndt, a specialist who would go on to become a double world time trial champion, but on that day Somarriba was not about to give up the jersey: she beat the German by three seconds. The favourites such as Luperini, Polikeviciute, Longo and Cappellotto were almost a minute behind her to start with.

In the sector of the motos, Somarriba worried some directors and commentators. Not because she was slacking, but because she was showing off his strength with a generosity that bordered on wastefulness, with two weeks of very hard racing ahead of him. But Somarriba knew the route by heart, she was in the lead on all the steep slopes, she took off on all the dangerous attacks, because she wanted to show her superiority from the start. With three kilometres to go to the finish in Gernika, the Lithuanian Polikeviciute attacked, followed by the Italian Luperini and Somarriba immediately jumped on her wheel. They opened up a gap. The Biscayan rider was never fast in the sprint and was third behind Luperini and Polikeviciute, but she extended her lead over all her rivals and once again wore the yellow jersey in Gernika, in front of her home crowd.

She dominated the Tour: she gave an exhibition going up and down the Tourmalet to win the breakaway in Campan, she also won the second time trial, she always came in first in the Alps and she won her second Tour more comfortably than the first.

Somarriba seemed unstoppable.

And four months later she was without a team. The Alfa Lum brand dropped its sponsorship, left many months of salary unpaid and left the riders out in the cold on the eve of a new season. After fighting for years to get the federal scholarships that would allow her to dedicate herself to cycling, Somarriba had gone to Italy because it was the country where women's cycling was most professionalised, but she always slipped into precariousness: she raced in teams with good directors, good technicians, good material, but with low salaries, non-payments and disappearances. In the Tour, the cyclists stayed in shabby hotels or in schools, they suffered long and very uncomfortable transfers between stages, as when they sailed from Corsica to the mainland and were only allowed to stay in the ferry's armchair rooms, with no rooms to rest in. Somarriba even recalled an occasion when the gendarmes prevented the cyclists from leaving the hotel because the Tour organisers had not paid their expenses. Four months after those glorious rides between Bilbao and Gernika, her greatest sporting euphoria and the peak of her popularity, Somarriba was left without a team and could not find one willing to hire the winner of two Giros and two Tours. She was not asking for millionaire contracts, just a decent salary. And there was no way.

During the winter she continued to train, looking for sponsorship and increasingly demoralised. In the end, the Deia newspaper set up a team with the co-sponsorship of the Pragma and Colnago brands, so that Somarriba was able to return to the Tour: she finished third and completed the year with a bronze at the World Championships.

Somarriba showed almost greater endurance in the winters, when she had to find grants and sponsorships year after year, than in the summers climbing the Tourmalet. In 2003 she managed to form another new squad, with an amalgam of Basque public and private sponsors: Bizkaia-Panda-Spiuk-Sabeco. With this team, which few trusted, Somarriba won her third Tour de France. And at the end of the season she achieved one of the few sporting dreams she was missing: she was proclaimed world champion against the clock.

Amidst the pains of her back injury, the precariousness and the obstacles, Joane Somarriba emerged (in pink, yellow, rainbow) as one of the best cyclists of all time.

Author: Ander Izagirre